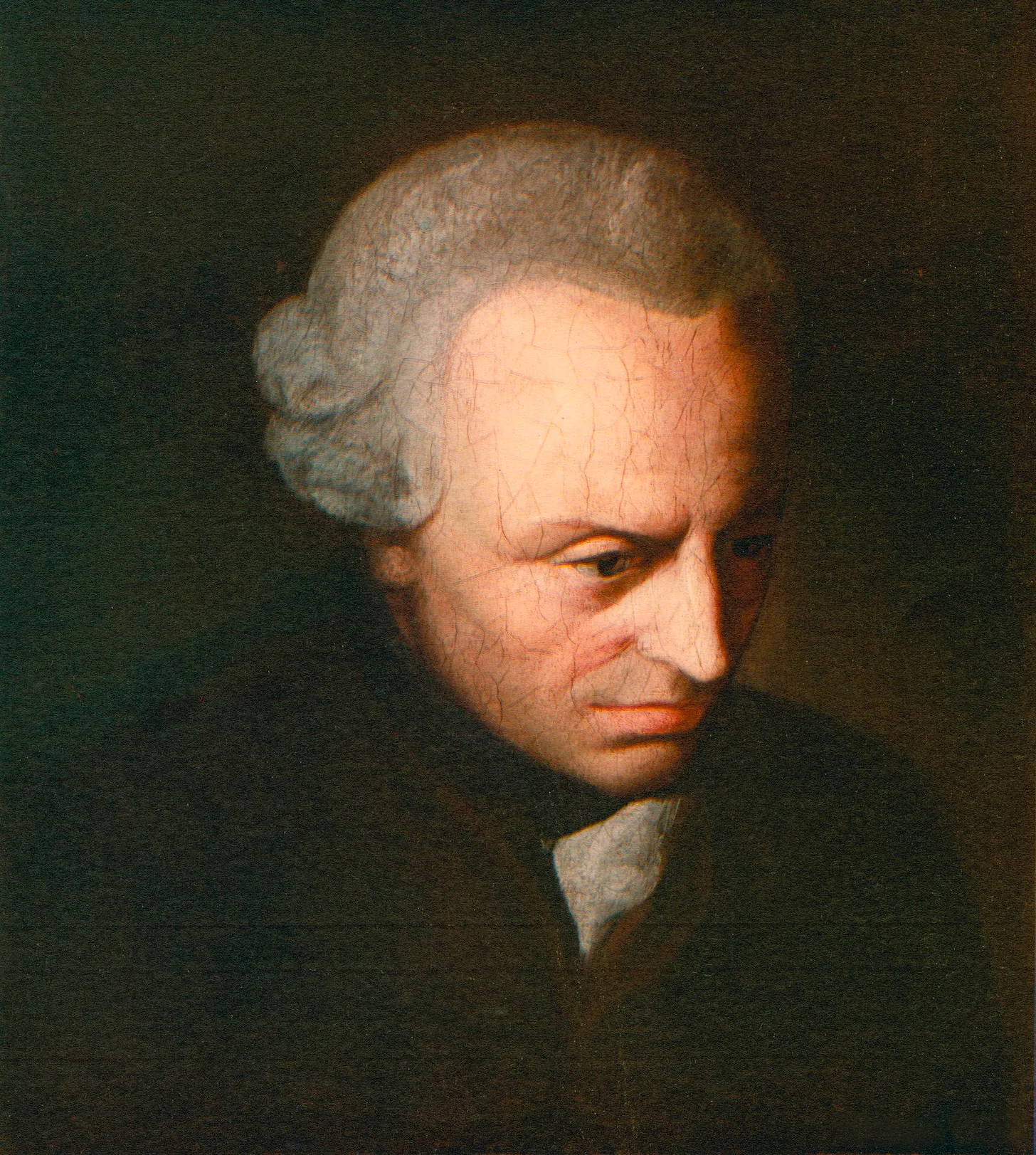

“What is the purpose of the United Nations? It has such tremendous, tremendous potential. But it's not even coming close to living up to that potential. For the most part, at least for now, all they seem to do is write a really strongly worded letter and then never follow that letter up. It's empty words and empty words don't solve war.” President Donald Trump, always the iconoclast, is the mouthpiece for the global resistance to the last 50 years of the rules based order. This conflict makes up the background of Marcus Willaschek's new introduction to Immanuel Kant, liberalism's most profound and original thinker.

Explaining Kant is a difficult task since his work is complex while at the same time enormously influential. My future wife asked me in the backyard of a bar one night to “Explain Kant to me”, which she attributes as the reason for the start of our relationship.

Kant is a towering figure in the history of thought. He has almost 35,000 entries on the academic archive philpapers.org, 12,000 more entries than Plato and 25,000 more than Nietzsche. He wrote on topics ranging from metaphysics, ontology, logic, physics, mathematics, and theology to politics, ethics, and aesthetics. His impact was so large scholars use Kant and his Critique of Pure Reason as the transition point from pre-modern and modern thought.

Willaschek in his new book seeks to be the definitive introduction to Kant. Kant is divided into 30 chapters that can be read independently if you need to use it as a reference for any parts of his philosophy. Willaschek's approach is to start with Kant's more accessible moral writing before getting into Kant's theoretical philosophy. This is also how Willaschek frames his interpretation of Kant, who continuously put the practical over the theoretical. Where introductions to Kant usually fail is that they prioritize one set of Kant's writings over others for the sake of brevity and accessibility or they repeat age-old myths about his life or philosophy at the cost of a holistic introduction. Kant overcomes both of these.

Immanuel Kant spent his entire life in Königsberg, now the Russian city of Kaliningrad. Königsberg is also known for inspiring Euler's creation of the field of mathematics called graph theory. It is also where Hannah Arendt lived for some time in her childhood. Kant never left his city, partly due to his weaker physical disposition and the difficulty of travel, partly due to his contentment learning about the world through books and papers.

Before there were tenured professors, intellectuals usually had to find funding for their pursuits through the church, the nobility, or the crown. Kant had none of these, and he started his career as a lecturer where he was paid based on attendance. Kant used this to his advantage, lecturing not just on philosophy, but on subjects such as anthropology and geology. The volume of his lectures, and if attendance is any indicator of skill, he was successful. Lecturing allowed him to stay in what is now called academia long enough to secure his desired chair in metaphysics and logic at the University of Königsberg, where he would call home for his entire career.

One of the myths of Kant the man that Willaschek dispels is the picture of the boring bachelor, the rigid scholar. In reality, Kant was a regular Königsberg socialite, making friends with the rising industrial class, a future mayor, pastors, philosophers, and poets. Willaschek writes “Kant was full of joie de vivre and enjoyed going out and gambling” and that he “moved in the most refined social circles.” It was at the death of a friend when Kant was 40, Johann Daniel Funk, and the influence of his new friend Joseph Green, a man of industry and habit, that Kant settled into a more regular and mundane lifestyle. However, Kant still played host to the intellectuals of his day after this, having regular dinner parties where they discussed everything except philosophy.

The topics of conversation in Kant's time were certainly the industrialization of Europe, the French Revolution, globalization through colonialism and trade, and the decline of the old values of tradition, religion, and hierarchy. The old was breaking down and the new was just beginning.

Liberalism as an ideology had not yet become the dominant set of norms. Kant was a great admirer of the French Revolution, although had the obvious reservations about the Reign of Terror. Willaschek tells us of a conversation with Theodor Gottlieb von Hippel, Kant defended the revolution as an experiment in humanity's march toward a more liberal world of freedom, to which Hippel responded “Oh, what a fine little experiment it is that involves butchering a royal family and beheading some of the finest people!” While the reverberations of the revolution were spreading through Europe, so was Kant's own revolution. In 1781, Kant published his magnum opus and cornerstone of his entire system. Just as the French Revolution executed the nobility, the rulers of the old order, Kant was cutting down the old rulers of philosophy. Heinrich Heine, the poet, wrote: “Our German philosophy is really but the dream of the French Revolution … Kant is our Robespierre.” and “Immanuel Kant, the arch-destroyer in the realm of thought, far surpassed in terrorism Maximilian Robespierre, he had many similarities with the latter, which induce a comparison between the two men.”

Why Kant's philosophy was revolutionary is where Willaschek is at his best in Kant. This revolution was that Kant inverted “the assumed relationship between the perceiving subject and the perceived object, an approach which placed the human subject at the center of the world.” It is no surprise that this is the strongest part of Willaschek's Kant. Willaschek is first and foremost a scholar of Kant.

His 2018 work Kant on the Sources of Metaphysics is a highly technical work on one of the major ideas of Kant's Critique of Pure Reason. The idea is that God, the soul, and the world, the major concepts of metaphysics, arise necessarily from logic and reason itself. Reason seeks the unconditioned from the conditioned. We can ask an infinite set of questions of what caused something. Reason drives us into the realm of metaphysics to concepts such as an “unmoved mover” (God) or an uncaused cause (spontaneity, freedom). Philosophers either answer this skeptically, saying that there is no God or freedom, and that there is just nature and causes all the way down. Or we answer in the affirmative, in favor of these concepts of metaphysics as answers to our metaphysical dilemmas.

Kant's philosophy paves a new middle path, between the skeptics and the dogmatists on these questions, but also between the rationalists and empiricists. The rationalists think, roughly, that reason and logic are the primary ways we can know the world, that knowledge is a priori. Empiricists rather rely on the senses and perception, the a posteriori, as the source of knowledge. Kant's phrase on this “Thoughts without content are empty, intuitions without concepts are blind.” The thrust of this idea is that both the empiricists and rationalists are one sided. For Kant, it is not an either or between both sides, but a both and neither.

Both sides are right that knowledge comes from reason and the senses. But, Kant says, reason actually structures our experiences, both are united in what Kant calls the synthetic a priori. That is, there are valid judgements of reason, but they are only valid because the human subject shares the same capacity for experience. Metaphysical concepts are only valid insofar as they contribute to the possibility of experience for the human subject. Since we cannot have any possible experience of immortality or freedom, it is not theoretically knowable Kant says “If, on the other hand, the object conforms to the nature of our faculty of intuition, I can then easily conceive the possibility of such an a priori knowledge.”

The downside for the rationalists is that there is no firm ground in reason for the concepts like God, the soul, and freedom, which were pivotal for centuries to the old, theological dominated ideology of Europe. Thus the Critique of Pure Reason was received as a largely negative work, although this is another myth that Willaschek dispels. According to Willaschek, Kant proves that there is a universal reason, it is “intersubjective” in nature. The importance of this idea is immense for Kant and Willaschek's holistic interpretation. Despite different perspectives and experiences (subjectivity) there is a shared reason that grounds what is valid for everyone, so there is still objectivity even without dogmatically appeals to God, freedom, and the soul or the senses and intuition. This universal reason underpins Kant's practical philosophy.

After the Critique of Pure Reason, which secured the foundation of his system, Kant moved onto his practical philosophy, starting with the brief Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals. The Groundwork contains the famous categorical imperative, which can be expressed succintly as “Act upon a maxim that can also hold as a universal law.”

Here again, Willaschek exposes many of the myths associated with Kant's practical philosophy. The first myth is that Kant's work is too rationalistic. Most critiques focus on the first of Kant's three formulations of the categorical imperative. Willaschek highlights Kant's more poetic and intuitive second formulation “Act in such a way that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never merely as a means to an end, but always at the same time as an end.” It is no wonder Kant's idea of a human as an “end-in-itself” is so enduring.

Another myth about Kant's practical philosophy is that it is too individualistic. Willaschek not only gives the reader the third formulation of the categorical imperative, the idea that we must act as legislators in a “kingdom of ends”, he also has an entire chapter dedicated to a lesser known work, his Religion within the Boundaries of Mere Reason. This is a later work by Kant, but it is pivotal to rounding out his philosophy. The first parts of the book contains detailed discussions about how his categorical imperative relates to human nature and the social. Willaschek writes “The treatise on religion, written eight years later, picks up on this idea and develops it into the notion of an invisible “kingdom of God on Earth” and a visible “true Church,” a term Kant uses to denote the community of all people, so long as they view their moral obligations as divine commands. In Kant's view, therefore, religion is the social side of morality.”

The last major myth that Willaschek takes on is that Kant has no concrete political philosophy. Especially since the founding of America, with the separation of church and state, the idea that morality and politics are two different spheres is dominant. Kant was ahead of his time. Kant wrote a separate Doctrine of Right in which he argued for a separate sphere of rules governing morals. The German word “recht” has a more complex meaning than right has in English, recht is concerned with all things related to law, justice, and individual rights. Philosophers like John Rawls, supposed allies of Kant, did him no justice by basing their political philosophy on Kant's Groundwork, even though it did popularize Kant's ethics.

The central problem of Doctrine of Right is that of coercion, when is coercion just? For Kant, any use of coercion that is a “hindering of a hindrance to freedom” is right, self-defense being the classic example. In this work, Kant stakes progressive positions on modern problems around the rights of state in regards to the public, especially welfare and public health. Kant was also a pioneer in theories around international law and refugee rights, the primary concerns of the United Nations. Willaschek notes the influence of Kant's more well known essay “Perpetual Peace” on Woodrow Wilson's League of Nations, the precursor to the United Nations.

Kant, however, is not pure propaganda about Kant as a liberal sage. Willaschek sprinkles throughout the book Kant's lowest moments as a thinker. Kant not only inherited but consciously articulated a hierarchy of races, even doubling down after critiques from eye witnesses of other non-Europeans published works to the contrary. Important thinkers such as Johann Gotfried Herder also were public in their criticism of Kant's racial thinking. Kant expressed a traditional patriarchal view of relations and qualities of men and women. More ambiguous are his positions on colonialism. Willaschek references Kant scholar Pauline Kleingeld's work where she argues that he later developed more anti-colonialist positions. He also made some controversial remarks about Judaism, such as “it is not strictly a religion at all” but rather a “secular state”.

Not only did Kant have contentious views on gender, race, and religion, he was quite condescending when it came to his critics. Willaschek describes how he dismisses the Leibnizian-Wolffian philosophers of his day as “dogmatists” and the neo-Platonist mystics as “enthusiasts”. Whether it was Herder's Metacritique or the criticisms by popular philosopher Johann August Eberhard, Kant only responded that they were deliberate misreadings of his work and resorted to ad hominem attacks. Willaschek says that this is not in line with the “perpetual peace” and middle-way attitude of his philosophy.

Willaschek simply dismisses these as character flaws and errors of Kant being not yet reasonable enough. But is this not a deeper issue, Kant being an individual representative of the strengths and weaknesses of liberalism?

Those contemporary critics of Kant were not much different than the modern manifestations of these liberal critics, something Willaschek points to himself. Willaschek paints Kant as a Macron-like figure in the history of philosophy, but he understates the problems of establishment centrism that we are so familiar with today. On one side, there are the rationalists and dogmatists, and the other the skeptics and the empiricists. Willaschek writes “Religious fundamentalists are a contemporary, atrophied iteration of the first, “objectivist” position, while superficial cultural relativism (“anything goes”) is a modern echo of the second, “subjectivist” viewpoint”.

When describing Kant's idea of the highest good, what the meaning is for Kant, Willaschek directly equates Kant's thought to core liberal values and ideas: “we have seen that perpetual peace represents the highest political good in Kant's eyes because it incorporates all other benefits within itself and safeguards them: namely, the rights and freedoms of the individual through the rule of law and a republican constitution; the common good through a system of (state-protected and -regulated) free trade; and states' rights and peace through a world peace order in the form a league of nations.”

Willaschek even goes so far to tie Kant to what is commonly known as neoliberalism, which is directly tied to the Trumpian counter-movement: “Hopes for the onward march of democratization worldwide and a lasting world peace order, which seemed realistic around the year 2000, have evaporated: in many locations around the world, politics is not characterized by democracy, progress, and peace but by the unscrupulous pursuit of power, the dismantling of democratic institutions and the rule of law, and warlike aggression. Man-made climate change is being denied by many people, and at the same its consequences are jeopardizing world peace.”

This is where Willaschek starts to contradict himself when it comes to his recurring yet subtle commentary relating Kant to present day politics. Willaschek is aware of the critiques of Enlightenment, using Adorno and Horkheimer's Dialectic of Enlightenment as his archetype. In this work, Adorno and Horkheimer argue that the horrors of the 1900s, the gulags and concentration camps, were not accidents external to the Enlightenment. Willaschek himself writes “Rather, it is a direct consequence of the Enlightenment itself, which reduced rationality and learning to exploitative mastery over nature before ultimately turning upon human beings themselves. Horkheimer and Adorno apply this criticism to Kant too, who actually meant economic independence when he talked about maturity: “The bourgeois in the successive forms of the slave-owner, the free entrepreneur, and the administrator, is the logical subject of enlightenment.”

Willaschek responds not much differently in substance than Kant did to his critics. Willaschek writes that Kant would deny that the subject of Enlightenment is the “slave-owner, the free entrepreneur, and the administrator”, it is humanity itself, “at least from a long-term perspective”. Willaschek's own words show that maybe liberalism does not know how to deal with the illiberal and unreason, or at least Kant's philosophy cannot.

Willaschek ends the book with a naive plea, reciting neo-Kantian Otto Liebmann's “Back to Kant!” as a way to get back into touch with the moral and philosophical roots of liberalism. However, it is hard not to agree with the sentiment of Adorno and Horkheimer, considering that it was almost impossible to not grow up reading Kant as a German in the late 19th and early 20th century, the era of Otto Liebmann, which was directly followed by the Third Reich and the Holocaust.

A few pages before his conclusion, Willaschek sides with the inheritor of Adorno and Horkheimer's Frankfurt School critical theory Jürgen Habermas as an example of someone we should look to for contemporary Kantian ideas applied to our political and social problems. In a lesser read work, Habermas had his own follow up to his teachers' Dialectic of Enlightenment, the Dialectics of Secularization. In 2004 Habermas debated Joseph Ratzinger, future Pope Benedict XVI. In this work, Habermas presents a thoroughly Kantian answer to Ernst-Wolfgang Böckenförde's question “Does the free, secularized state exist on the basis of normative presuppositions that it itself cannot guarantee?”.

Ratzinger follows after Habermas and poses a problem that the Enlightenment struggles with and Kant overlooked. It is well known that there are “pathologies of religion”, Kant set out to purify and excise in his work the dogmas and biases of the church and religion. But Kant, and arguably Willaschek, do not give due space to what Ratzinger calls the “pathologies of reason”. Kant, and Willaschek in his scholarly work, has shown that reason runs into conflict with itself necessarily and generates metaphysical concepts. When it comes to practical reason, especially our political and social relations with our citizens and neighbors, does reason not produce its own conflict? Does it not generate unreason, its double, and create more violence as reason and rationality tries to infinitely dominate the irrational, the remainder?

Kant created a middle way for philosophy out of the conflict of the Middle Ages and Early Modern era. But as we have seen in the theoretical critiques of Adorno and Horkheimer or Ratzinger and in the practical manifestations of the Third Reich in Germany or Trumpism in the 2020s, that liberalism is an ideology like any other, with its own dogmas and violence. Kant is a great philosophical introduction on one of our greatest thinkers and will undoubtedly benefit those who read it, but the liberal current that runs through the text will leave the reader wanting for something that can say more for us today.