Kant makes the transcendental status of this issue plainest in the following passage, though here he speaks of a 'logical law of genera' instead of the 'transcendental affinity of the sensory manifold':

If among the appearances offering themselves to us there were such a great variety – I will not say of form (for they might be similar to one another in that) but of content [sic], i.e., regarding the manifoldness of existing beings – that even the most acute human understanding, through comparison of one with another, could not detect the least similarity (a case which can at least be thought), then the logical law of genera would not obtain at all, no concept of a genus, nor any other universal concept, indeed no understanding at all would obtain, since it is the understanding that has to do with such concepts. The logical principle of genera therefore presupposes a transcendental [principle of genera] if it is to be applied to nature (by which I here understand only objects that are given to us). According to that [latter] principle, sameness of kind is necessarily presupposed in the manifold of a possible experience (even though we cannot determine its degree a priori), because without it no empirical concepts and hence no experience would be possible. (KdrV, A653–54/B681–82; emphases added.)

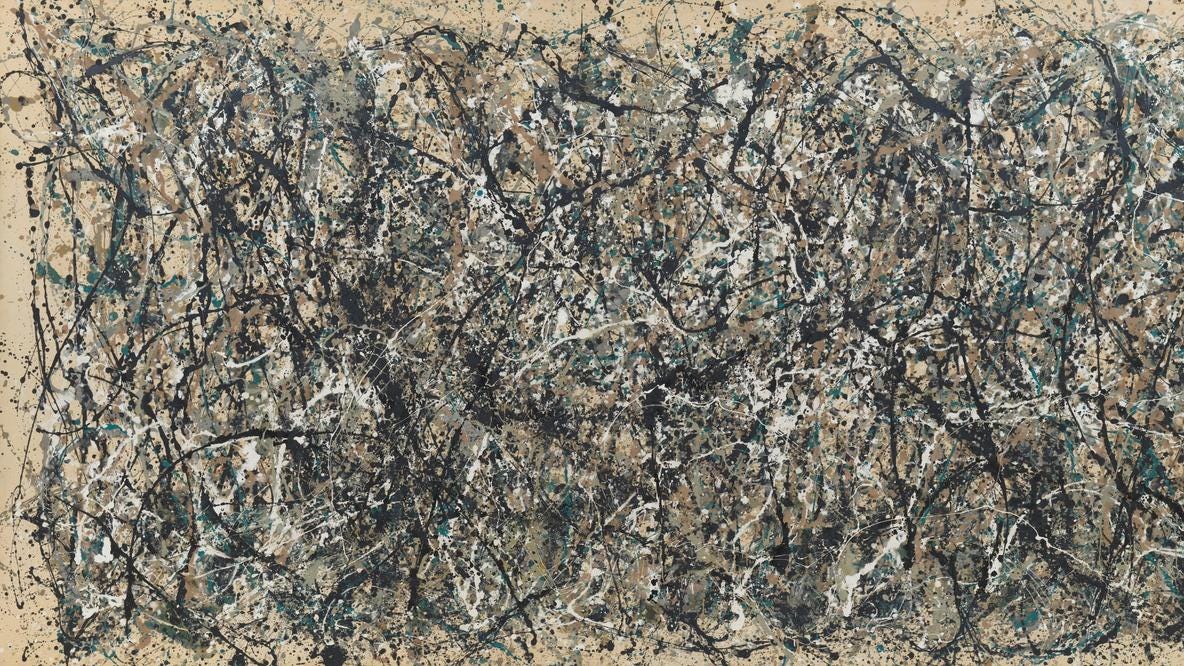

Despite Kant's shift in terminology, it is plain that the condition that satisfies the 'transcendental principle of genera' at this fundamental level is the very same as that which satisfies the 'transcendental affinity of the sensory manifold': In the extreme case suggested by Kant, where there is no humanly detectable regularities or variety within the contents of our sensory experience – call it 'transcendental chaos' – there could be no human thought, and so no human self-consciousness, at all. Kant establishes this necessary transcendental condition for self-conscious human experience by identifying a key cognitive incapacity of ours: our incapacity to be self-conscious, even to think, even to generate or to employ concepts, in a world of transcendental chaos. We can recognize Kant's insight only by carefully considering the radically counter-factual case he confronts us with: by recognizing how utterly incapacitating transcendental chaos would be for our own thought, experience, and self-consciousness. Recognizing this, like recognizing any of the incapacities that characterize human cognition, requires transcendental reflection.

Kant was responding here to David Hume. Hume sees only pattern and habit in nature, but no "laws of nature". As a follower of the rationalist school at the time, specifically the German Leibnizian-Wolffians, Hume's challenge to the certainty of natural laws was a call to action for Kant. After Hume, the question was is there any sure footing to place philosophy upon?

The quoted passage above is less an argument than an "intuition pump". The passage above from KdrV, the Critique of Pure Reason, is at the end of the book. In the main part of the book, Kant presents two arguments for his transcendental idealism. The first is what Anja Jauernig calls his "master argument" or what Karl Ameriks called the "long argument". There are, however, "short arguments" that are made throughout the book in support of Kant's transcendental idealism as well. One such set of short arguments are Kant's antinomies, which show that taking transcendental realism to be true leads to contradiction. If transcendental realism were true there would be no contradictions, hence the short argument to transcendental idealism as the only alternative.

The entire passage above is from a paper by Kenneth Westphal. I am not sure of the first time I heard the phrase. I assumed it was a work of Henry Allison, but could not find it in any books or papers of his. However, the phrase has stuck with me from the original reference.

Kant contrasts his new position of transcendental idealism with what he considers all of philosophy's prior (and implicit) position, transcendental realism. Transcendental idealism takes objects to be conforming to the mind, whereas realism takes the mind to conform to objects. For Kant, as he learned from Hume, this means that if our position is one of transcendental realism, then empirical objects end up as merely ideal. By contrast, with transcendental idealism, where objects as they appear to us are real. This allows Kant to put natural law, for example Newton's laws, back on a sure footing.

The idea of transcendental chaos gets at the crux of what Kant was trying to correct in philosophy. For there to be any experience whatsoever, experience which we indeed are having (if this sounds like Descartes, then you would be in agreement with Béatrice Longuenesse and Martin Heidegger), there must be something minimally necessary about the mind-world connection and the subject-object relation that makes experience possible. Otherwise, we would be lost in chaos, not able to form any experience.